Having spent the summers of his youth doing farmwork in the US - the closing and militarization of the border is an offensive concept to Jose Luis (left.) "We don't want to live in America - you don't need to fear us. We just want to do the jobs your people won't do and then go home..." He added, "but we must stay because crossing the border is too difficult."

Migrants pray in the church at Altar prior to connecting with their smugglers (coyotes) who will guide them through the desert for a price.

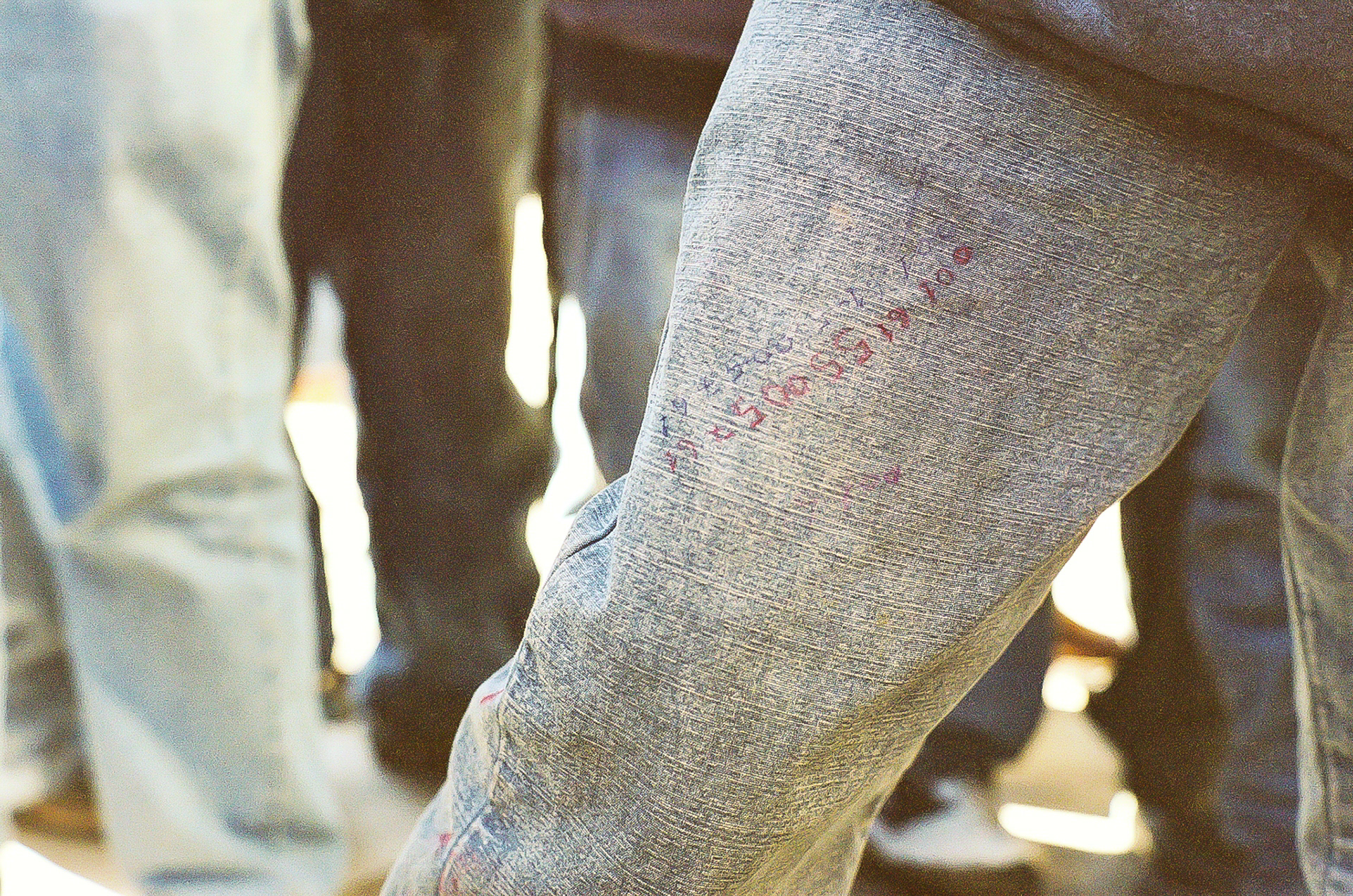

Scrawling on the pants leg of Michalandro, a migrating teen from Chiapas, Mexico. They are phone numbers for his sister who lives "near Canada." His reasoning for writing them on his pants was - "if anything bad happens to me, if I die, at least they can tell my sister." In actuality, the area code is near Nashville, TN. I called the number a few months after this picture was taken. Michalandro had not yet arrived.

Crosses marking a death of a loved one hang on the border fence in downtown Nogales, Mexico. On each cross is written the name of the deceased and how they died. Many die from dehydration, others from robbery or molestation. Some causes are unknown. An interesting point of trivia is that the holed panels these crosses hang on are recycled landing strip plates sent back from Kuwait and Iraq after the first Gulf War. They were used to build temporary airports on the desert sand.

Graffiti on the border fence in downtown Nogales, Mexico. Depicts a US border patrol agent shooting a Mexican migrant, execution style.

Neighborhood women are the backbone of finance and labor for the services provided by Casa de la Misericordia. Here they are cleaning up after a lunch meal.

Noemi Peregrino-Gonzalez, a Mexican nun, accompanies our group and gives cultural insight into the problems of economics, poverty and migration as she overlooks an invasion community of migrant laborers in Nogales, Mexico.

Hillside "invasion community" near foreign owned factories in Nogales, Mexico. These communities are called "invasion communities" because landowners offer them up in a land grab for the sole purpose of allowing people to build rudimentary living quarters without charging for the land. Once the shacks and houses have been established "service fees" are established by the landowner based on the amount of land and the quality of the house. This particular "invasion community" has no running water or sewer service. A water truck provides potable water two or three times a week for sale.

Children's toys on the Mexican hillside looking toward the US. Houses abut the fence in this "invasion community." In addition to the fence infrared cameras monitor human traffic 24/7 along this stretch of the border.

Memory shelf in the dining hall of Casa de la Misericordia - a neighborhood mission helping to feed and educate the children of migrants and border area workers in Nogales, Mexico.

Resilliano, a young man of 17 at the DIF Youth Repatriation center in Nogales, Mexico. He was caught by border agents in Arizona crossing into the US and will be bused back to his home town.

Rev. Robin Hoover gives last minute instructions to replenishment truck driver Marissa Rice as she heads to the desert to refill Humane Borders watering station barrels.

Rev. Robin Hoover of the First Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in Tucson, AZ is the organizer of Humane Borders which has 70 water and aid stations throughout the US side of the Sonoran desert. These aid stations help migrants survive their most prevalent cause of death: dehydration. On the day of this visit he has just encountered a group of "Minutemen" border vigilantes at a public speech. Fearing a more violent encounter, Rev. Hoover was still brandishing his pistol when we rang the bell for entrance to the church.

T.K. Estes (Tucson) and John Virgin check the water level in one of Humane Border's fresh water emergency stations in the Sonoran desert south of Tucson, AZ.

A Humane Borders aid station in the Sonoran desert south of Tucson, AZ. The blue flag signals to migrants that fresh water is available if they are in trouble. Most migrants avoid the stations, fearing border patrol monitoring. Yet, in desperate cases of dehydration these stations ultimately save lives.

During my final semester in seminary, classmate John Virgin and I headed to Tucson, Ariz., for our “transcultural immersion” in U.S./Mexico border issues. The trip was also an opportunity to work on a photo essay I'd envisioned as part of this educational experience.

Within minutes of landing we were loaded into a van and on our way to Mexico for nearly a week. Our experience primarily consisted of time spent in locally supported training and education centers, seeing border town encampments – called “invasion communities,” visiting border employees, staying with Mexican families and touring border control/immigration processing centers.

What we found were people – migrants – heading north for the promise of lucrative border jobs in Mexico and/or a chance to enter the U.S. An overwhelming majority of people we spoke with were migrating due to poverty and trade inequities that cause their locally grown produce to be sold for much less than U.S. imports – especially corn.

With no hope for improving economic conditions, these desperate people – including women, young children and unaccompanied teenagers – from Mexico and Central America make the often dangerous journey north to seek a better life in manufacturing jobs or an even more perilous border crossing.

All images in this essay were taken with a Leica M6 camera and 50mm Summilux lens. Films were Kodak T400CN and Fuji Superia 400.

Note: Images from this project appeared in the documentary “Beyond Borders: Faith and Action in the Arizona Desert” produced by Rebecca Woods.